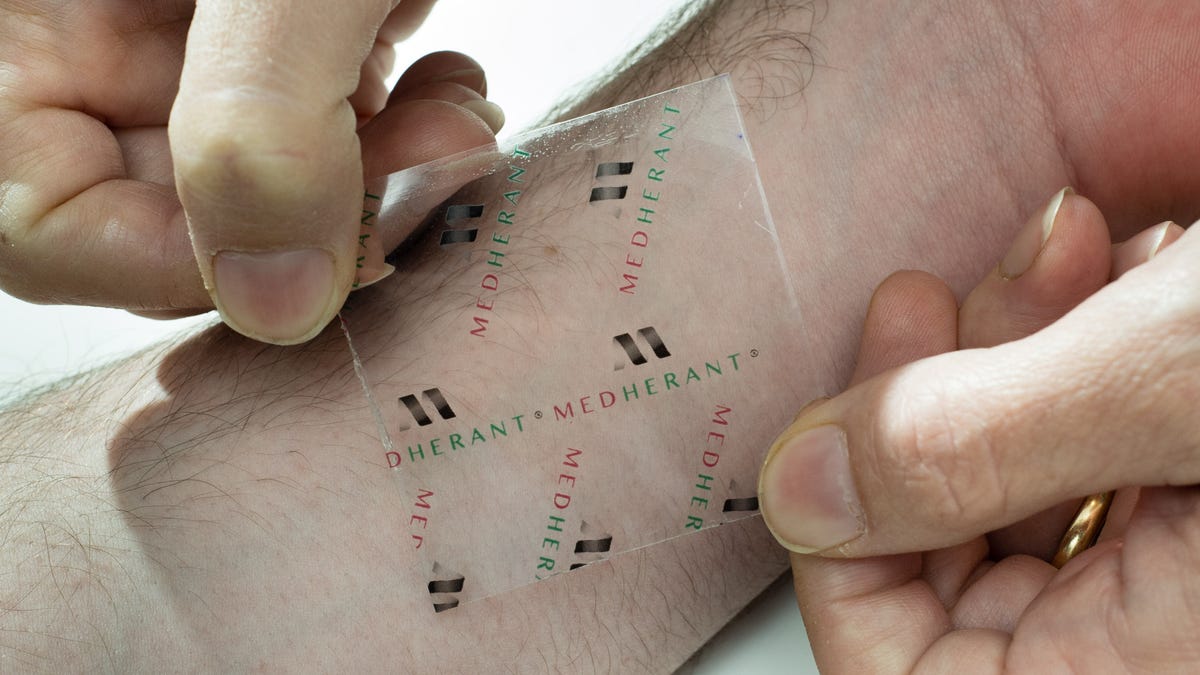

Where does it hurt? Newly developed patch technology could change the way drugs are delivered through the skin.

Freelance writer Amanda C. Kooser covers gadgets and tech news with a twist for CNET. When not wallowing in weird gear and iPad apps for cats, she can be found tinkering with her 1956 DeSoto.

Amanda Kooser Dec. 8, 2015 10:40 a.m. PT 2 min read

You pulled a muscle. Ice and ibuprofen. That headache came back. Relaxation and ibuprofen. Your mild arthritis is acting up again. Heat and ibuprofen. Ibuprofen is a popular over-the-counter pain killer, but it's generally taken as an oral pill, which may cause stomach upset in some people.

Researchers at the University of Warwick in England have developed an ibuprofen patch that delivers a concentrated dose of the drug directly through the skin. The university calls it the "world's first ibuprofen patch."

Patches are already in use for delivering certain types of medicine, such as nicotine patches for smoking cessation or scopolamine patches for motion sickness.

Topical ibuprofen gels can be applied to the skin to relieve pain, but the patch is designed to provide a more controlled dosage in a convenient format. The back of the patch contains ibuprofen incorporated into a polymer matrix that is sticky and adheres well to skin.

The patch is unusual in that it can carry a high dose of ibuprofen and deliver medication for up to 12 hours, according to a statement December 8. The patch can hold a drug load (weight of the drug compared with the total contents of the dose) as high as 30 percent, which "can be 5 -10 times [. ] that found in some currently used medical patches and gels," the University of Warwick notes.

The university calls the transparent patch "cosmetically pleasing," if you're concerned about how the medication might impact your fashion.

In a nifty bit of med-speak, Nigel Davis, CEO of bio-adhesive company Medherant (a co-developer of the patch), calls the patch a "next-generation transdermal drug-delivery platform." The patch development could have implications for other drugs beyond ibuprofen, and further testing is planned.

This isn't the first time researchers have tried to improve on current gel-based transdermal delivery methods for ibuprofen. Scientists have experimented with clove oil and tested the use of liquid microemulsions for better permeation through the skin. If the new ibuprofen patch proves to be as effective as its creators say, then it could offer a valuable expansion in pain-relief options.

It sounds like the new patch technology could be especially helpful for localized pain, like pulled muscles or arthritis, or for people who are sensitive to taking the oral version of ibuprofen. Davis said Medherant expects to bring the delivery system to the market in about two years in the form of over-the-counter pain-relief patches.